Best Practices for Collaboration Between Industry and Academe

The 12 academic disciplines represented in the survey were dominated by electrical, industrial, chemical, mechanical, and computer engineering. The 14 technology application domains were primarily represented by process, energy, and manufacturing. The nine practice sectors were substantially represented by industrial suppliers, industrial users, service providers, and vendors. The eight academic sectors involved were primarily research and graduate programs. Interestingly, most of the research entities listed their focus as application rather than pure science.

Understanding collaboration

Collaboration can take many forms, all of which can be mutually beneficial. Collaboration is an activity whereby individuals work together for a common purpose to achieve a common target benefit. Essential skills include trust, tolerance, self-awareness, empathy, transparency, active listening and conflict resolution. Collaboration is not people working independently and following their own paths. Collaboration means accepting the experience of the others in the joint effort.

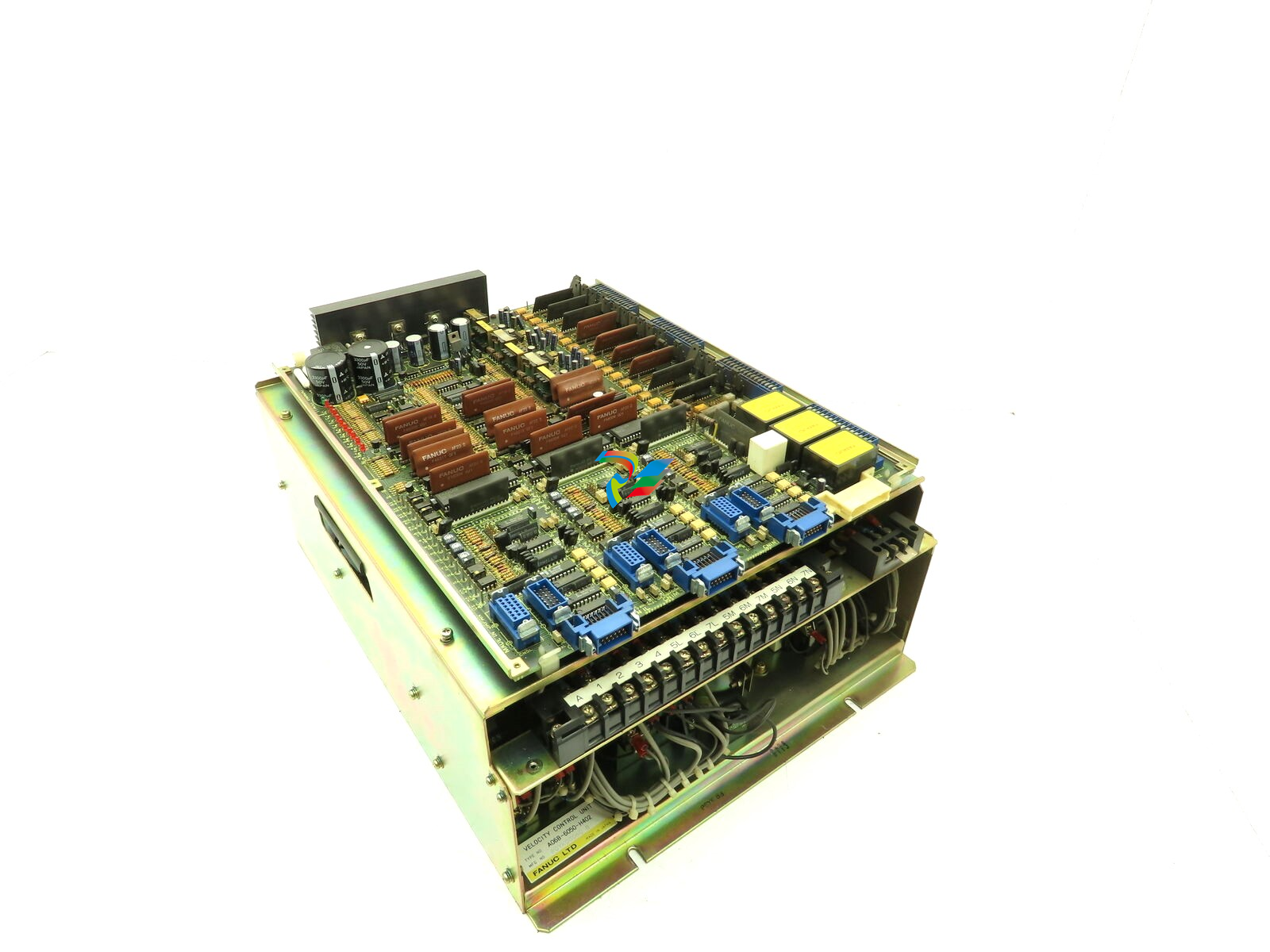

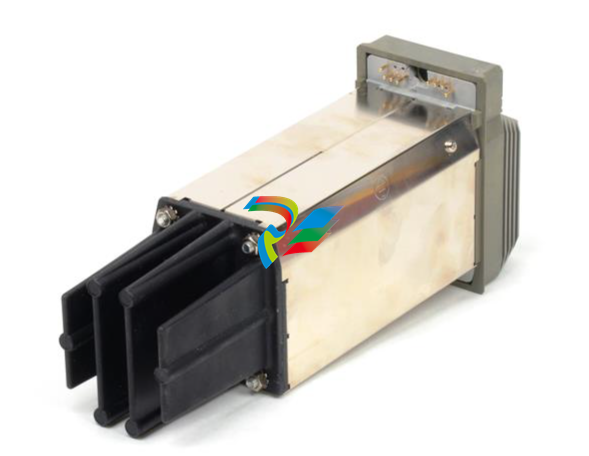

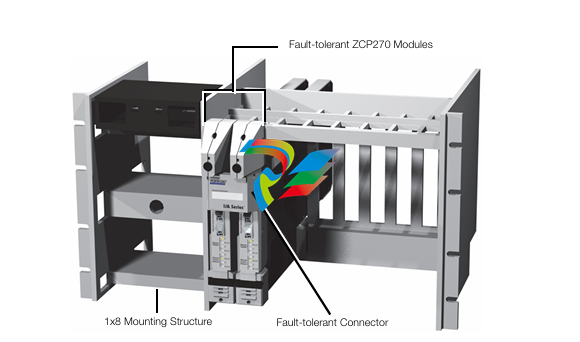

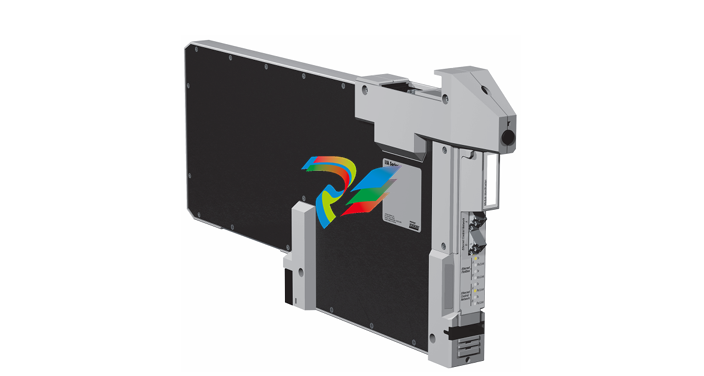

Examples of collaboration include industry practitioners helping in classrooms by providing guest lectures on topics and application perspectives often omitted in education. They could provide case studies for teaching examples or student projects. Industry could help in laboratory experiences by providing equipment and technical support.

With such collaboration comes many benefits: The teaching faculty comes to better understand the needs of the practice. Respectful relations are formed for possible future problem-solving benefit. Contact with students gives industry folks a recruiting advantage. Students benefit from the exposure and enjoy the real-world insight.

As a reciprocal, industry could host academic associates at invited seminars or short courses for employee continuing education and skills development. The experience shapes the academic focus, improving both teaching and research.

Another example is industry-sponsored research projects for undergraduate or graduate students. Preferentially, these are precommercial investigations designed to help practitioners answer their questions or explore a possibility that might seem promising. The sponsorship could be one on one or within a consortium, and the students and faculty would be allowed to publish the results.

Industry also could hire faculty on an individual basis to solve a problem or to help develop a product, or it could engage equipment, faculty, and students to provide support through a university contract. Here, intellectual property (IP) concerns related to rights to inventions and patents would restrict academic publication. Myopic lawyers within both the industry sponsor and the academic institution seem to place IP possession above the benefit of collaboration and argue that their side should have exclusive rights. The IP impasse is often a barrier to collaboration, but when agreement can be reached, product and process development is enhanced.

The five players and their motivations

The survey reveals that five separate groups are involved in any academic practice collaboration. Each group must have an incentive to participate and to invest its resources to make a collaboration successful. The collaboration needs to be structured so each of the players experiences a benefit that justifies its investment. Each group also has its own culture and way of interacting. A collaboration must permit those diverse ways to synergize. The five groups are students, faculty, academic institutions, practitioners, and practice entities. Here is what motivates each to collaborate.

Students

Students are seeking practical knowledge and experience about the industrial context, which will lead to career and employment opportunities. Students are excited to work on real-world problems, to have access to state-of-the art hardware and software, and to relate the theory learned in class to specific practical situations. Students want to work with industrial mentors to gain in-depth understanding of the nontechnical side of practice, such as soft skills, project management, and market-driven decision making.

Faculty

Top incentives for faculty are professional development and funding. Professional development includes staying current with the state of the art in the field, selecting relevant research topics, validating ideas, having access to actual data, networking, and maintaining visibility through academic publications. Research funding is required to build a research group, support equipment and travel, and provide summer income. Industry-funded projects provide the means to support and sustain an academic group. Sponsored projects identify ideas faculty can use for their more science-oriented research.

Other incentives for faculty are practical relevance of the curriculum and personal satisfaction. Collaboration with practice makes faculty more comprehensive teachers and mentors to their students, due to exposure to first-hand knowledge about technology, practices, expectations, and opportunities. Industrial collaboration can provide a unique and advantageous perspective on the state of the art. The ability to steer the students in the right direction naturally leads to personal satisfaction.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_lVjBYb.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)