Adding ‘Industrial’ to Cybersecurity Education

As organizations mature their operational technology (OT) security approach, they tend to move from a focus on technology to a focus on building a program to, finally, building a workforce that can run the program and operate the technology. This natural progression has been described as the “Industrial Cybersecurity Awakening Model” (Figure 1).

It can take four years—and sometimes much longer—to reach Stage 5 of the model where organizations intentionally develop an OT security team. The International Society of Automation Global Cybersecurity Alliance (ISA GCA) supported a three-year research project to create a consensus-based OT security body of knowledge and has released a 125-page document and other resources. “Curricular Guidance: Industrial Cybersecurity Knowledge” describes the stages of the model and helps ensure OT security leaders can work with education and training providers that follow a consensus-based OT security body of knowledge.

In the recent past, ransomware has been a significant driver in the awakening. Those who have been in touch with their local industries know that automotive manufacturers, salad processors and paper makers have suffered ransom demands that shut down process lines and resulted in a relatively rapid leap from Stage 1 to Stage 3. The aftermath of a breach generally leaves one or two individuals (often the electrical engineering professionals who have now been asked to pick up cybersecurity) asking for the resources required to move the “OT side of the house” to stage 4.

Management of some organizations has contented themselves with the belief that a technology investment alone will get the job done. Stage 3 is as far as they are willing to go. But other organizations, especially those with far-flung operations, are advancing to Stages 4 and 5.

At stage four, the IEC 62443 series of standards provides powerful concepts such as the industrial automation and control system (IACS) lifecycle, the IACS principle roles, system types and maturity levels that are key to building a good OT security program. IEC 62443-2-1 recognizes the need for cybersecurity training by including the following requirements:

Development of a cybersecurity training program

Providing cybersecurity procedure and facility training

Providing cybersecurity training for support personnel

Validating the cybersecurity training program

Revising the cybersecurity training over time

Maintaining employee cybersecurity training records (64443-2-1 Req. 4.3.2.4.1-4.3.2.6.4).

When organizations begin to grapple with these training requirements, they begin to recognize serious impediments, such as:

Lack of a widely recognized OT security body of knowledge

Lack of consensus-based OT security work roles

Lack of validated OT security competencies per work role

Lack of role-specific OT security training

No discussion of OT security competencies required of non-security personnel.

The role of workforce development

OT security leaders attempting to tackle this issue find a complex and often foreign world of workforce development literature and guidance.

Plethoric government agencies and professional training providers offer workforce development models. Within these models, definitions of key terms often conflict, and some terms have changed official definitions within the models over just a few years. It can be overwhelming to sort through.

With these challenges in mind, a working group composed of qualified representatives from industry, government and academia embarked on a three-year research project to review existing OT security workforce development guidance, and where lacking, establish a consensus-based foundation.

In 2019, the Idaho National Laboratory (INL) and Idaho State University (ISU) convened 15 qualified industrial cybersecurity professionals in ISU’s Simplot Decision Support Center, where they engaged in the bias-eliminating nominal group technique to identify five archetype industrial cybersecurity job roles, and initial knowledge categories not normally covered in traditional cybersecurity education.

The results of this effort were published in November 2021 as “Building an Industrial Cybersecurity Workforce: A Manager’s Guide” which included job descriptions, key tasks and hiring advice. Recognizing that despite its strengths, this document did not constitute a consensus-based body of knowledge for an emerging cybersecurity specialization, the INL, ISA Global Cybersecurity Alliance (ISAGCA), and ISU decided to validate, critique and expand the document by involving a broader group of qualified experts.

In Spring 2022, the ISACGA administered a survey to professionals with interest or experience in industrial cybersecurity. The survey included up to 363 input items and received inputs from 170 qualified respondents. The survey questions, responses, analysis and decisions are available for public review, examination and additional analysis on the ISAGCA website. While this is an impressive level of transparency for a curricular guidance effort, the most exciting part is the guidance itself.

The 125-page document is an essential reference for students, instructors, administrators and industrial cybersecurity practitioners. It is organized around the analogy of a building with three components represented in Figure 2: an environment, a foundation and a superstructure.

The Industrial Operations Environment describes the contexts (business, geopolitical, professional and industry) within which industrial control systems and industrial cybersecurity exist. The Industrial Control Systems Foundation describes the elements (instrumentation and control, process equipment, industrial networking and communication, and process safety and reliability) that compose an industrial control system. The Industrial Cybersecurity Superstructure describes the elements (guidance and regulation, common weaknesses, events and incidents, and defensive techniques) that most immediately and intuitively pertain to assuring an industrial control system.

Each component is organized into categories, topics and subtopics to reach a level of reasonable granularity—up to six levels deep. While some topic names are identical to those found in traditional cybersecurity contexts, the study describes the unique or special considerations of those topics for industrial and OT environments.

OT security leaders attempting to achieve Stage 5 can now work with education and training providers that rely on a consensus-based OT security body of knowledge.

Resources

The International Society of Automation Global Cybersecurity Alliance (ISA GCA) supports the author’s research and provides these related resources:

Whitepaper: “Curricular Guidance: Industrial Cybersecurity Knowledge,”

Webinar: “Curricular guidance to develop a new generation of industrial cybersecurity professionals”

The ISAGCA website contains survey questions, responses, analysis and more.

Training a cyber-infused generation of automation professionals

What would you say if someone asked how to best move towards a secure digital future for critical infrastructure and industrial automation?

In late July 2016, I was contacted by my master’s thesis supervisor (Dr. Corey Schou) from Idaho State University (ISU) where I had graduated 10 years earlier. He asked whether I would be interested in teaching a course in ISU’s new Industrial Cybersecurity Program.

As I had spent the first decade of my professional life in industrial cybersecurity, I thought this sounded intriguing. I cleared what I thought would be a one-night-a-week teaching commitment with my employer (FireEye/Mandiant) where I had just been appointed as director of the industrial control systems security virtual business unit and started preparing course content for “Risk Management in Cyber-Physical Systems.”

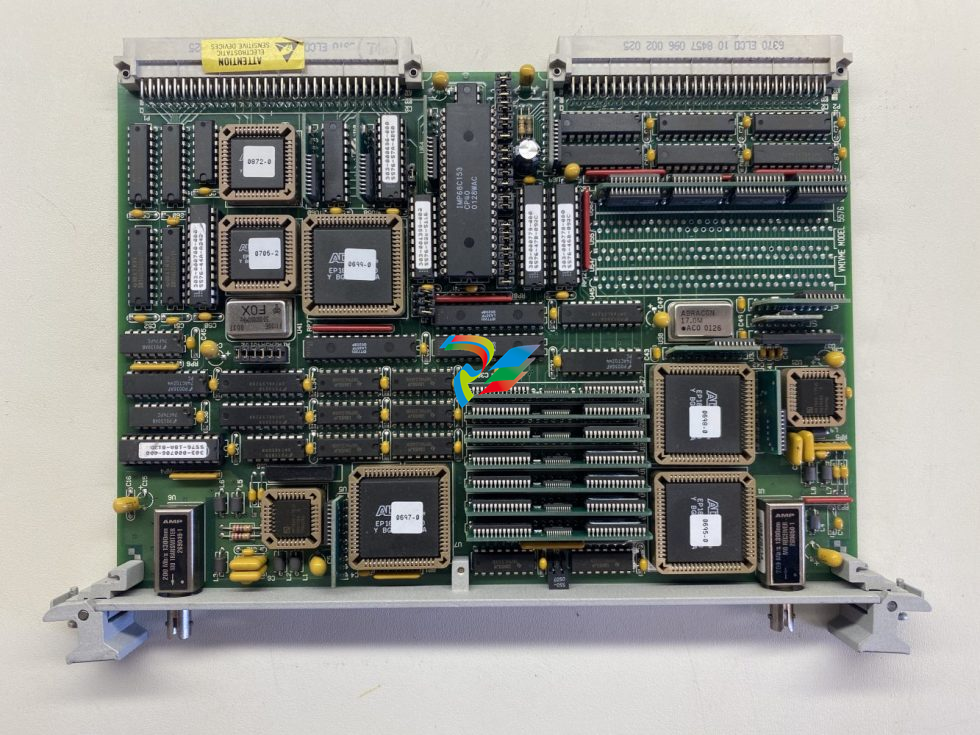

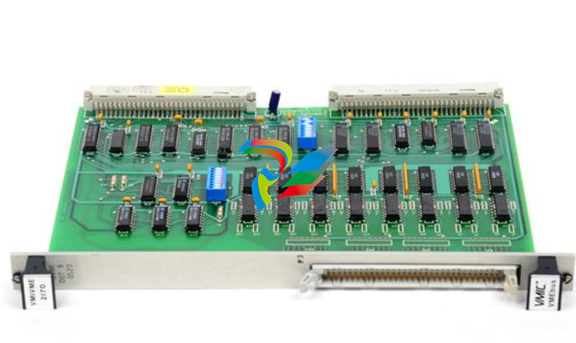

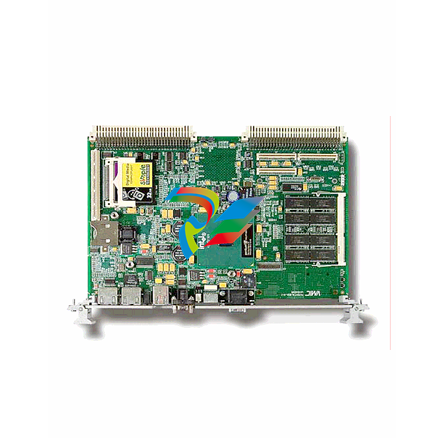

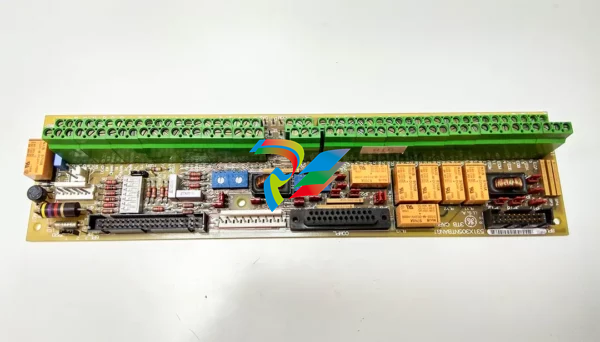

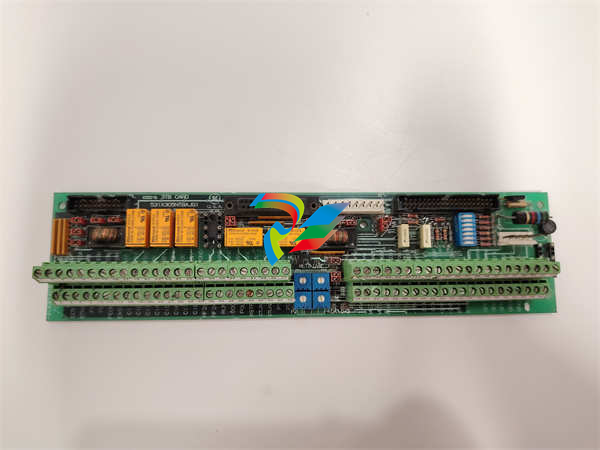

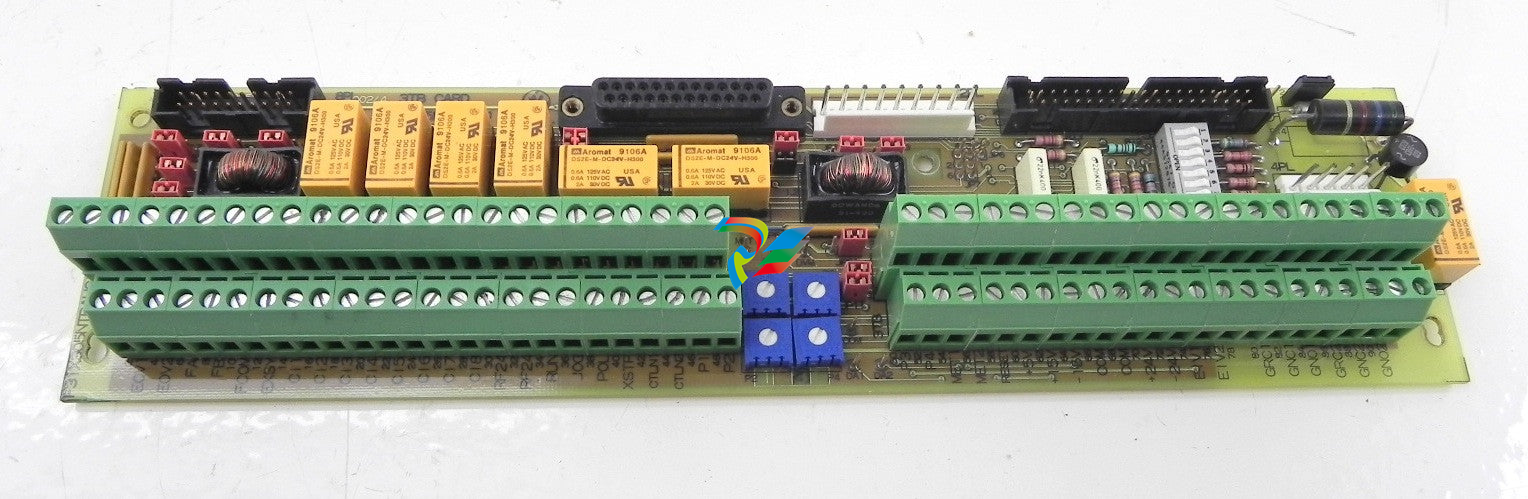

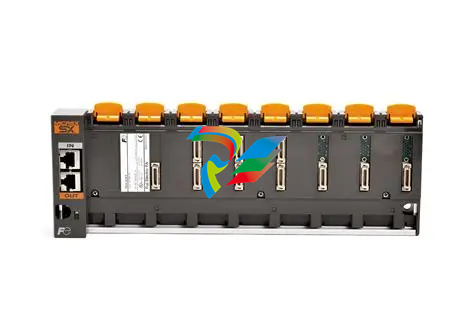

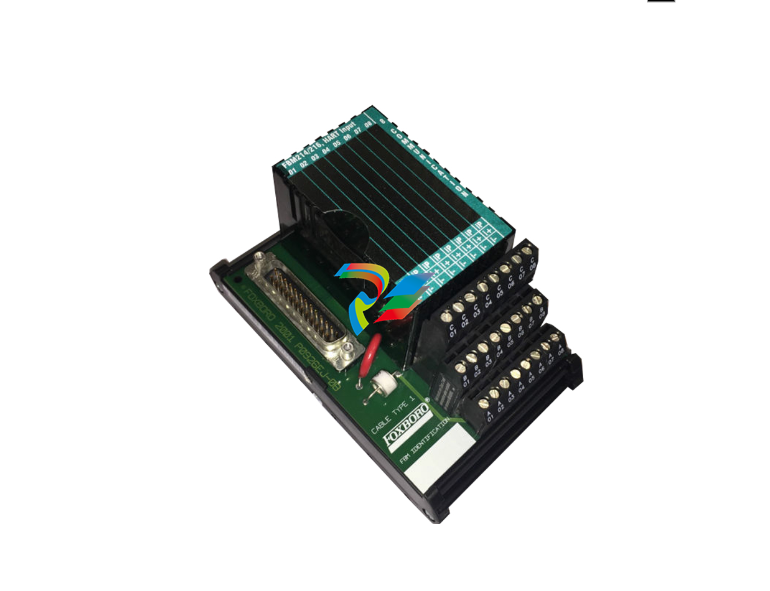

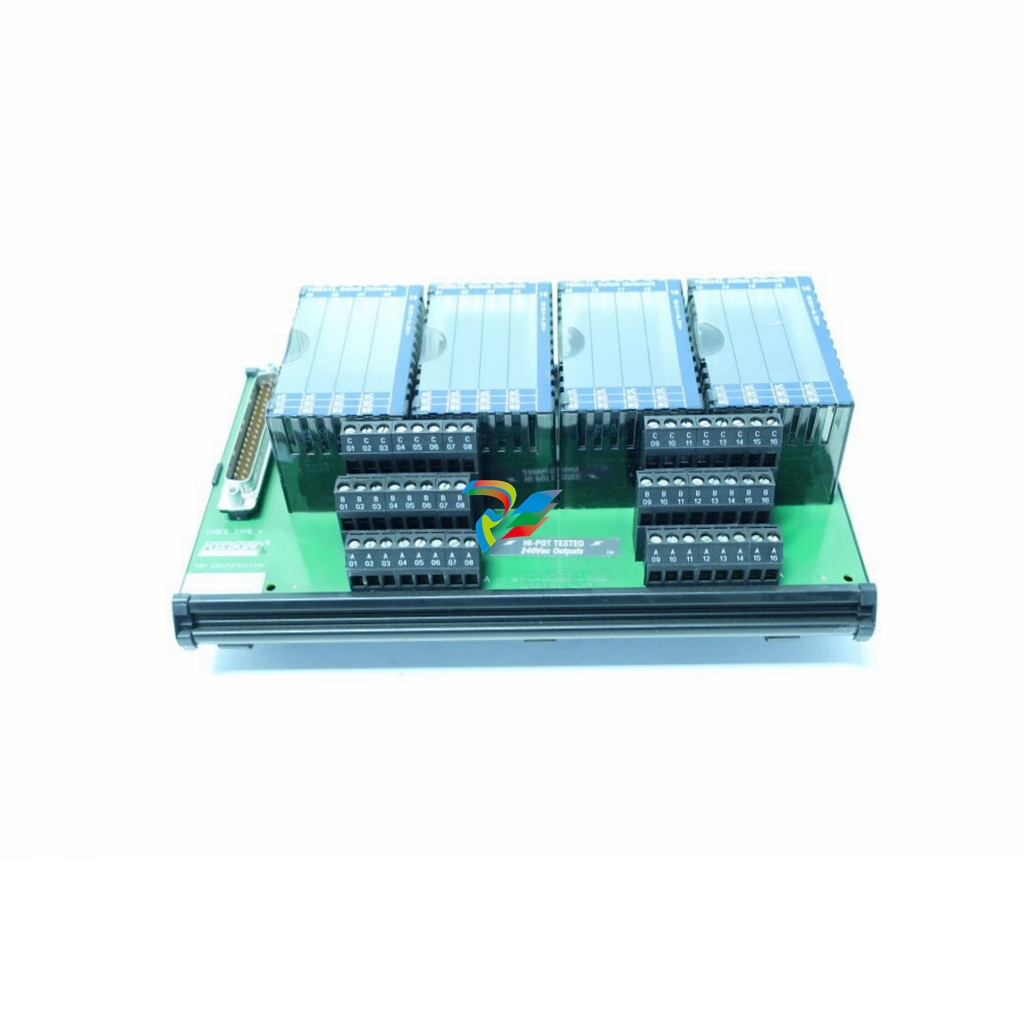

I was unfamiliar with ISU’s Energy Systems Education and Training Center (ESTEC) where the program was housed. So, when I walked into the ESTEC building and saw the fantastic hands-on educational equipment including programmable logic controllers, variable frequency drives, transmitters, pumps, valves, motors, conveyors and pipes, and talked with the experienced instructors, I realized how special this opportunity could be.

ESTEC is a department-level center featuring five distinct engineering technology programs: electrical, instrumentation, mechanical, nuclear operations and industrial cybersecurity. It features 40,000 sq. ft. of educational laboratory and classroom space spread across four buildings on ISU’s main campus in Pocatello, Idaho.

ESTEC was founded in 2007 with the primary objective of expanding ISU’s existing industrial automation program to meet the growing demand for qualified technical professionals at the Idaho National Laboratory. Hundreds of ESTEC graduates work across the country in places like Simplot, Phillips 66, Chevron, Alyeska Pipeline, Columbia Electric Distributors and many other industrial firms.

When I started teaching, I thought to myself, “Wow, the Idaho State Board of Education has approved the country’s first industrial cybersecurity degree program. ESTEC is already a leader in preparing professionals to go into critical infrastructure environments. We need to teach cybersecurity to these students. This is exactly what the country needs. It’s exactly what the world needs.”

I believed it so firmly that I quit my high-paying job at FireEye to become ESTEC’s Industrial Cybersecurity Program Coordinator. My responsibility was to build the program from the ground up.

Over the next seven years, I authored courses, made curriculum proposals, visited high schools to recruit students, submitted and won grants, graded assignments and exams, and hired faculty. I helped place graduates at national-level employers such as the INL, Accenture, Savannah River, National Renewable Energy Laboratory and HDR Engineering, among others.

One of the accomplishments I am most pleased with is that the Industrial Cybersecurity Program at ISU is stackable. “Stackable” means that students can come into the program directly from high school and earn an Associate of Applied Science degree within two years, or they can come into the program from a variety of engineering or operational technology (OT) degrees—including electrical, instrumentation, mechanical and nuclear operations, as well as on-site diesel power and information technology (IT) systems. Students have completed the program from each of these entry points.

One key to this stackability is that the industrial cybersecurity courses are offered as upper division credit (300 and 400 level), meaning they can provide a pathway to a bachelor's degree. After completing industrial cybersecurity courses, students are pointed to a handful of management-oriented upper-division courses including technical writing, project management, supply chain management and organizational behavior. Once students satisfy their general education requirements, they earn a Bachelor of Applied Science in Cyber-Physical Systems.

ISU has taken program development very seriously. In 2022, the Industrial Cybersecurity Program was recognized as a National Security Agency-designated cybersecurity program of study; and, in 2024, the program achieved ABET accreditation. So, how we are going to move towards a more secure digital future in critical infrastructure and industrial automation? I’d say we have to start with the people—the future workforce.

The Industrial Cybersecurity Program at ISU is an outstanding model for how to do this. Through interdisciplinary stackable pathways, we are developing a new generation of automation professionals capable of seamlessly moving between IT, OT and cybersecurity domains.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_lVjBYb.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)