Managing SCADA During a Municipal Water/Wastewater Capital Project

Automation continues to play an increasing role in providing critical infrastructure including public water and wastewater facilities. Gone are the days of operators driving from site to site to turn valves and start or stop pumps as part of normal operations. Instead, we now use sophisticated supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) systems to automatically control and monitor the wide range of facilities that provide the drinking water and wastewater services we all depend on.

Building this critical infrastructure involves much planning, design and resources, not to mention many people with a wide variety of skillsets. This article provides an overview of the typical workflow involved with designing and building a municipal water/wastewater capital project, and the role that automation professionals play.

It’s a team effort

Good projects are always a team effort. No matter what methodology is used—traditional design-bid-build, design-build, design-bidbuild-operate, etc.—the common element is a wide variety of individuals and skillsets that need to come together to execute a successful project. Obviously, having a common goal, ensuring all parties work together, and ensuring the plant works—as well as ensuring everyone gets paid—are all of paramount importance.

The coordination of these efforts is usually undertaken by a group of project managers: One acting for the owner, one acting for the design team, and another acting as part of the construction team. It is the project managers who oversee the overall timeline and do the important tasks of controlling the schedule, scope, cost, and quality aspects of the project. Historically, most project managers at this level come from a civil engineering/ construction background. Civil engineers are generally not specialists, but typically will have a broad background that allows them to have a deep understanding of what is needed for each phase of the project and who will be needed to carry out the work. The project managers will then bring in various specialists as needed during the duration of the project. If a project involves SCADA in any way— which is pretty much a foregone conclusion these days—automation professionals will be needed throughout the project.

Scoping the project

Most municipal water/wastewater projects start with a study to confirm the need and timing for the upgrade (or new facility). The study is typically followed by securing funding, and then the development of a charter to define the project.

Once a project charter has been developed, the first task for the utility is to develop a detailed scope of what the project will include (and not include) and the intended plan for staging the work. To do this, a terms of reference (ToR) document is typically created for each of the major project teams. For a traditional designbid-build project, the ToR will provide a task-based overview of what aspects the design team will be handling. The design team will, in turn, develop the builder’s scope in the form of contract drawings and specifications.

Fast facts about SCADA

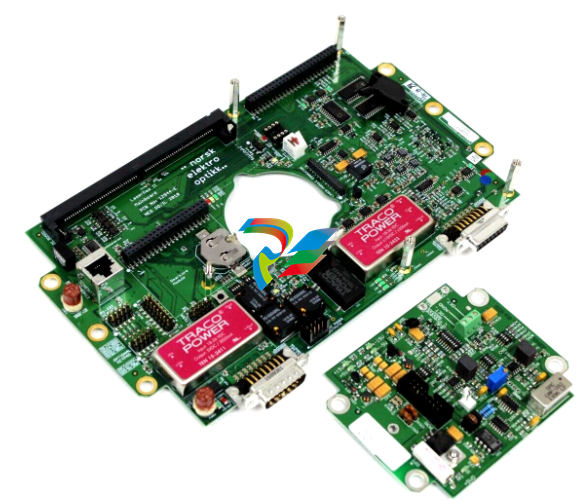

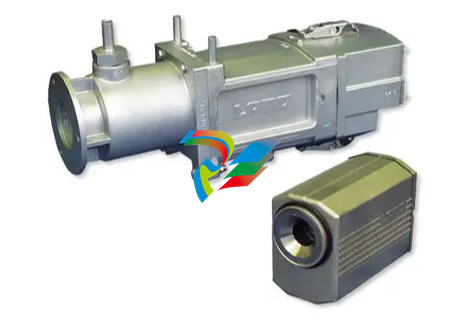

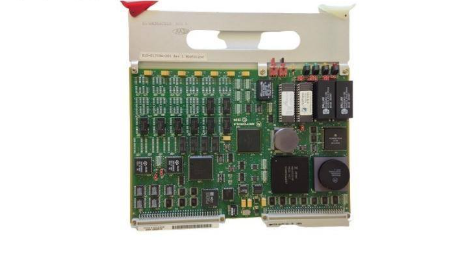

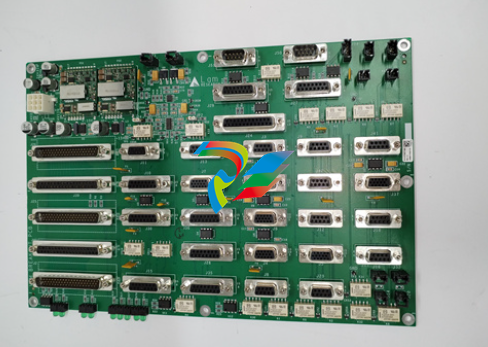

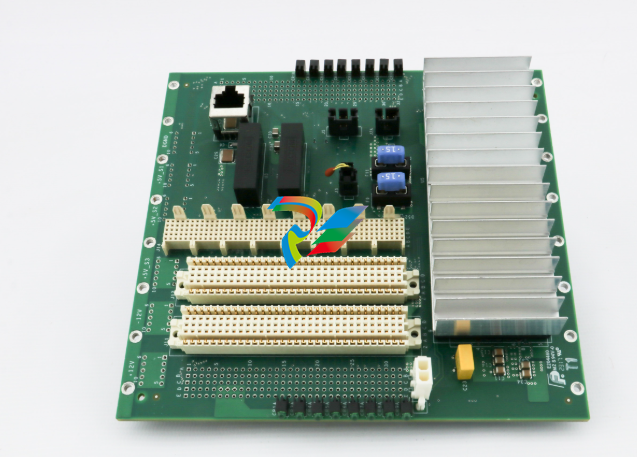

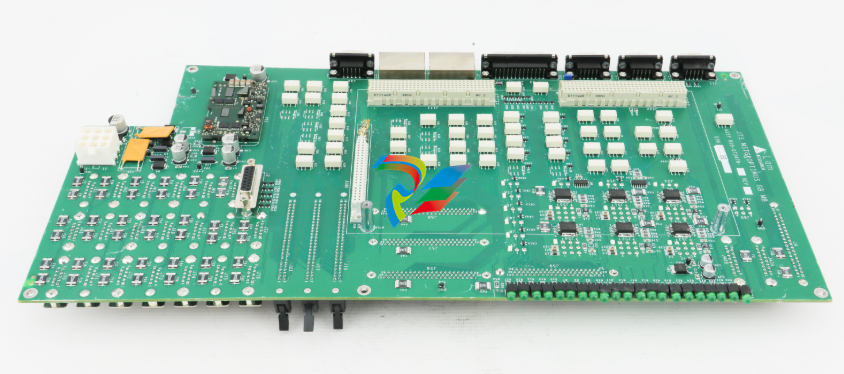

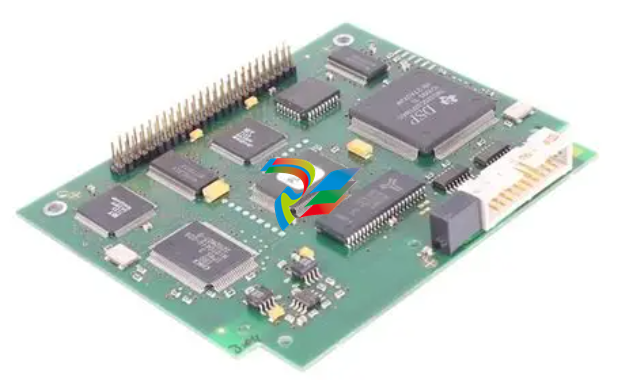

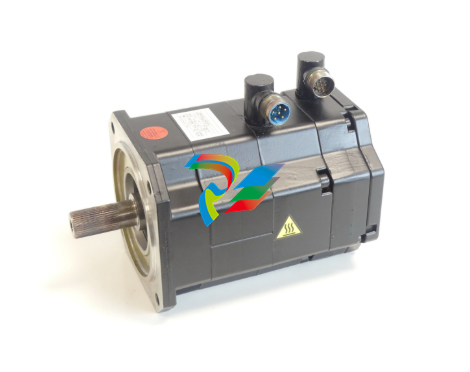

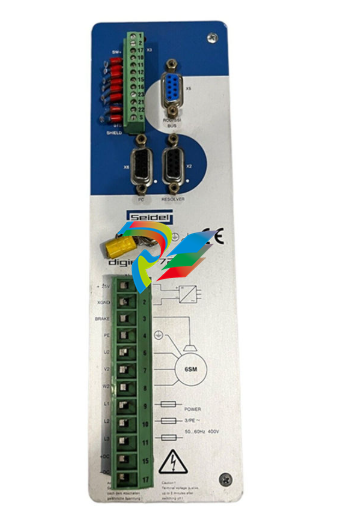

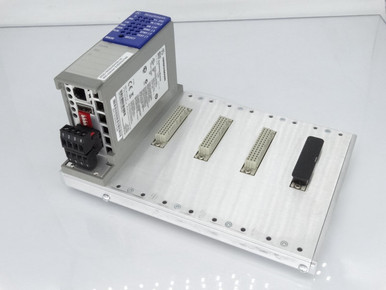

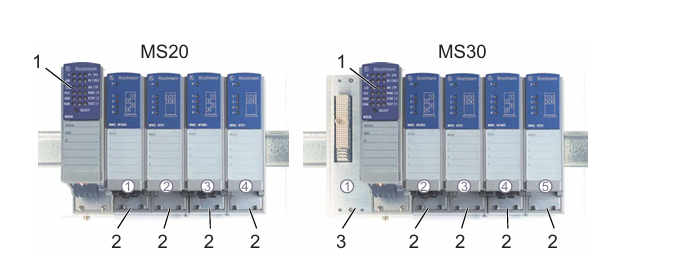

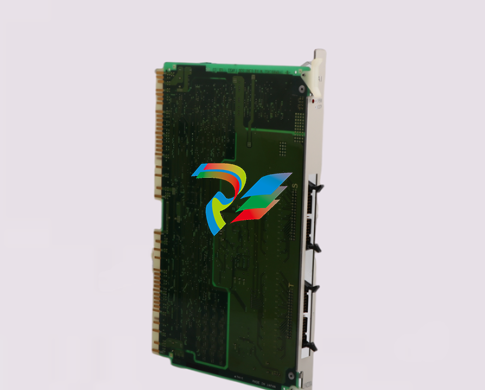

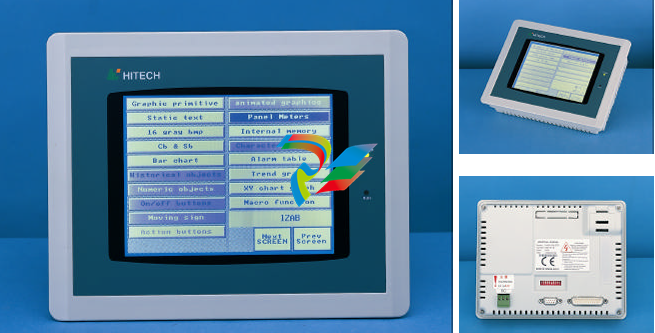

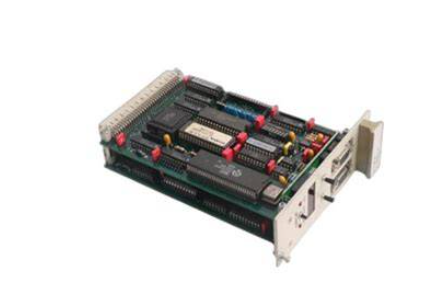

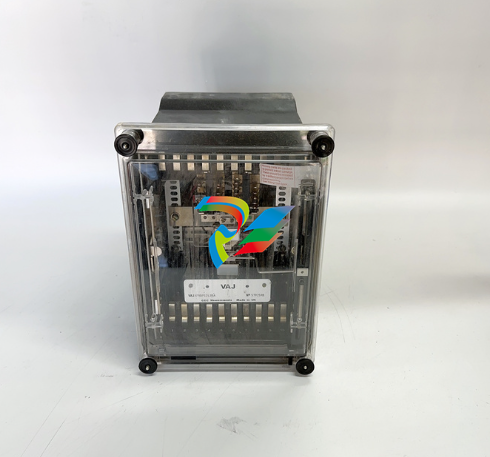

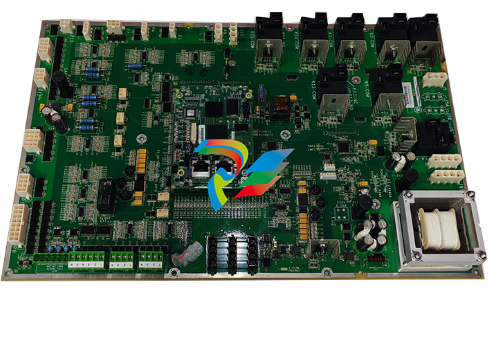

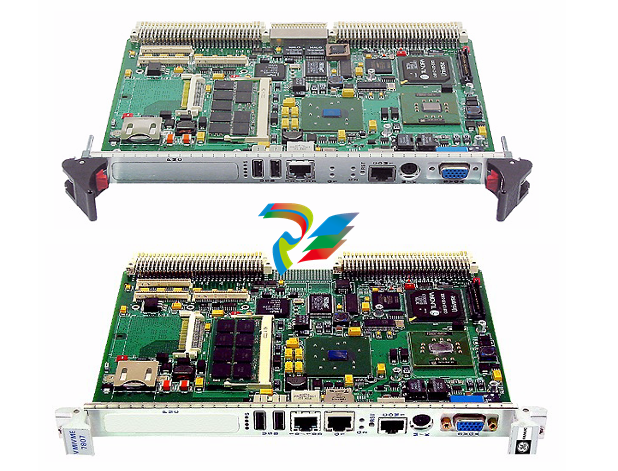

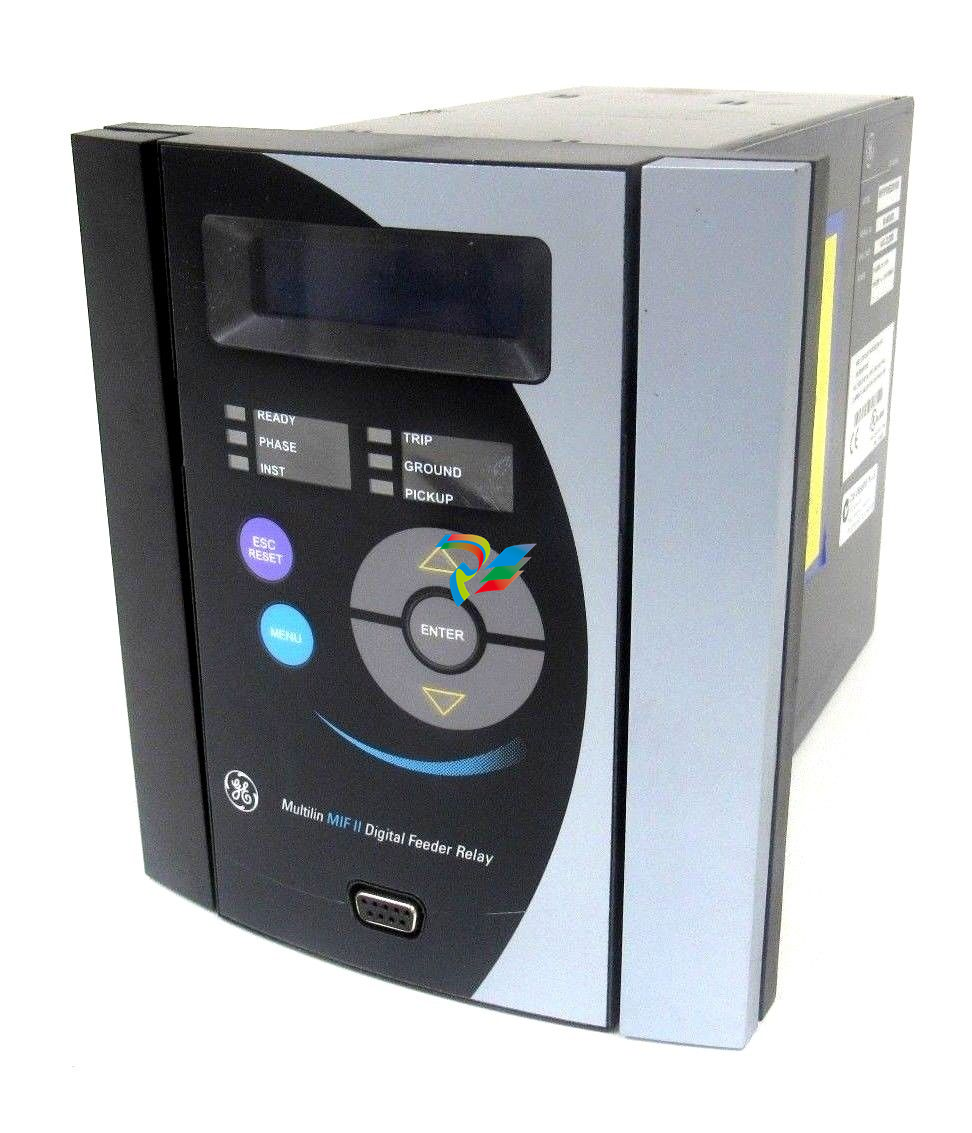

In the municipal water/wastewater sector, automation systems are referred to as SCADA systems and typically include instrumentation, signal wiring, programmable logic controllers (PLCs), motor control centers (MCCs)/motor starters, actuated valves, the control network, servers, workstations and alarm callout systems.

SCADA systems can be implemented in the municipal water/wastewater sector using a variety of technologies including PLCs with human-machine interface (HMI) software, distributed control systems (DCSs), Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT), and proprietary controllers.

Once installed, SCADA equipment in the municipal water/wastewater sector is expected to have a service life of 20 to 30 years, which is considerably longer than many other industries.

From the design team’s perspective, the ToR document will outline the design goals and provide a list of the deliverables and services the owner is expecting. A typical ToR includes task descriptions such as collecting background information, developing a design brief, preliminary design, various detailed design stages (e.g., 50%, 75%, 90%), and creating a ready-for-construction set of drawings and specifications, as well as administering the construction contract. In effect, the ToR for the design team forms the basis for many of the stages of a typical municipal infrastructure project. A summary of typical project stages is listed in Figure 1.